The world is, and was, a scary place. Humans long for a glimpse of the future. Something to help keep the dark waters at bay. Today people crunch data trying to dig out signals in the noise. Back in the ancient world, folks asked the gods. Well, they asked oracles or seers to help out. One did not ask the Sibyls, but tried to find meaning in their words.

Oracles were communication conduits for the gods in sacred locations all over the ancient world. They were consulted. Sibyls would spontaneously utter their predictions in all sorts of ecstatic ways unasked. Seers would see the future using a variety of techniques.

On the Greek island Dodona, priests and priestesses in the grove sacred to Zeus interpreted the rustling of oak leaves. Zeus also spoke to them through the chiming of bronze objects hanging in the sacred trees. Homer’s Odysseus once passed through and asked if he should go home to Ithaca in disguise. The epic poem The Odyssey would have been much shorter if he did not. The Argo, the famed ship of Jason and the Argonauts, was built with holy oak pinched from Dodona. The prow of which was able to speak with a human voice and would rely prophecies.

Trophonius oracle was demanding. The seeker had to live in a certain house for a period, bathe in the River Herkryna and live off of sacrificial meat. Then the seeker would sacrifice to a bunch of gods by day, and that night cast a ram into a pit sacred to Agamedes, and drink from the rivers Lethe and Mnemosyne. Finally they would descend into a terrifying cave that frightened the wits of out them. The freaked out seeker would sit on the chair of Mnemosyne and their ravings would be recorded and interpreted. Herodotus says this was around the 2nd millennium BCE.

Erythaea had a sybil or two. One predicted the Trojan War. Another the coming of Christ. Her prophecies were written on leaves and arranged so that the initial letters of the leaves always formed a word. Sybils were all over the Mediterranean.

Cumae also had a sybil who presided over the Apollonian oracle at Cumae. She prophesied by singing the fates and writing on oak leaves in the Aeneid. (Rumor has it she played Apollo. He offered her immortality in exchange for her virginity. She changed her mind then Apollo was like, oopsie – you didn’t ask for eternal youth. The classic gotcha!)

The Delphi Oracle survived into modern consciousness. The temple of Apollo at Delphi was home to the most famous oracle for centuries. She raved in a frenzied state induced by vapors rising from a chasm in the rock. Her gibberish was then interpreted into poetic dactylic hexameter verse. The ethylene creeping up into the innermost sanctuary might have done it. Gods apparently speak in vaporous ways.

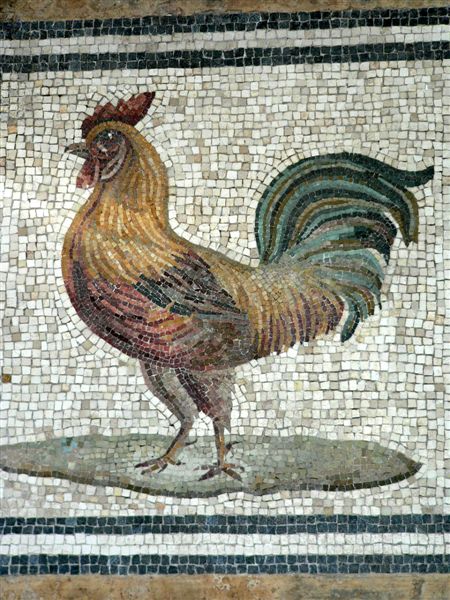

Oracles might have been young virgins from noble families huffing volcano fumes. Divination was big back in the day and realm of seers. Inspecting entrails of sacrificed animals, reading the flights of birds, interpreting thunder and thunderstorms, reading bubbles in urine, mucking about with eggs, and interpreting randomly overheard words were all game. My all time favorite is alectryomancy – divination by chickens.

Pecking at grain spread out on the ground was observed by pullarius (priest of the sacred chickens). If the chickens ate it avidly while stamping their feet and scattering it around – things were good. If they refused to eat or drink – that was bad. Before the ceremony the chickens were caged without food for a certain amount of time. These sacred chickens came from the Greek island of Negreoponte.

Chickens

Modern domestic chickens started their journey to Rome in Southeast Asia between 12,800 and 6,200 years ago. They took a different path from their red jungle fowl cousins based on current genetic evidence. Chickens leave very little archaeological evidence. G. Gallus domestic bones are hard to distinguish from their cousins. Scavengers leave little behind. Stratigraphic displacement frequently occurs. A Neolithic bone from Bulgaria turned out to be 5000 years younger than the age based on archeological stratigraphy.

There are three types of evidence that show the march of chickens in the Mediterranean world – written records, art, and physical evidence.

Written Records

Victorian lexicographer E. Cobham Brewer said Nergal, the Babylonian god of war, death, and disease, meant “Dunghill cock.” This led to the belief that chickens were hopping around in 2000 BCE in the Indus Valley. Nope. There is no archeological evidence that chickens were in Mesopotamia prior to the ninth century BCE. Those pesky Victorians!

Modern research suggest that Nergal (𒀭𒄊𒀕𒃲) in Sumerian means “Lord of the big city” not ‘dunghill cock’ as Brewer supposed. There isn’t any confirmed reference to chickens on cuneiform tablets. The Akkadian word tarlugallum (𒁯𒈗𒄷 ) comes from the Sumerian word darlugal ( 𒁯𒈗𒄷 ) which is literally “bird or fowl of the king”.

Dar meluḫḫa, mentioned on mid 3rd millennium BCE cuneiform tablets, was thought to mean chickens but its literal meaning is “francolins from meluḫḫa”. Francolins are a cousin of the chicken in the Galliformes Phasianidae family. Meluhha is the Sumerian word associated with the Harappan civilization located in modern-day Pakistan, northwestern India and northeast Afghanistan.

A modern reassessment based on zoo archaeological evidence implies that chickens first appeared after the Harappan civilization. The bird was described as dark-colored, which may make it a black francolin (Francolinus francolinus) or a gray jungle fowl. Both species were common in Indus Valley and their remains are indistinguishable.

Chickens appear in Vedic texts, the oldest known scriptures of Hinduism, after ∼1200 BCE. This doesn’t help Frederick Everard Zeuner’s theory of them being around in the Indus Valley in 2000 BCE. His theory in ‘History of domesticated Animals’ was based on bone fragments found in Indus Valley locations that were compared to modern chicken bones. Modern research has not found any evidence to support this claim.

A “land of the chickens” (probably referring to Media, located in modern northwest Iran) is mentioned in the royal inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser III (745 to 723 BCE). The phrase, “chickens being seen in the city” appears in Šumma ālu (a series of a collected number of cuneiform text from the seventh century BCE). The text references are well after 2000 BCE.

Pharaoh Tuthmose III (1479 to 1425 BCE) mentions a tribute from Mesopotamia of four birds that “gave birth every day,” which once were thought to be chickens. More likely they were geese or ducks. The “earliest chicken” reported from a contemporaneous New Kingdom Theban tomb dating to 1550 to 1070 BCE, was actually a duck.

Limited chicken consumption shows up in Roman laws against luxury in 161 BCE. Roman author Columella wrote extensively about chickens in his Red Rusticae Libre from the 1st century BCE. Cato the Elder (200 BCE), Varro (116 to 67 BCE), Palladis( 400 CE), and Pliny all mentioned chickens. Chickens must have been on the peninsula by 200 BCE.

Art

Chickens showed up in art starting in the 4th century BCE.

Heraldic and regular roosters were found in Etruscan necropolises centuries after chicken remains started being included in the tombs.

- Fiorellini tomb (second half 5th century BCE) – cockerel images

- del Gallo tomb (i.e. cockerel tomb) (late 5th century BCE) – heraldic cockerels are depicted on the tympani of the tomb back walls.

- Tomb 4813 (5th century BCE) – heraldic cockerels are depicted on the tympani of the tomb back walls

- Triclinio (early 5th century BCE)

- Stele Fiesolana (early 5th century BCE) from Travignoli (Pontassieve, Florence) has a cockerel image located in the same position as that of the Triclinio Tomb

Several necropoles in the Paestum area (Campania), dated to the second half of the 4th century BCE, included tombs for both sexes contained cockerel representations. These tombs are located in the necropoles of Andriuolo, Gaudo, Vannullo and Capaccio Scalo.

- Paestum (Campania) cockerel representations second half of the 4th century BCE

- Andriuolo

- Gaudo Vannullo

- Capaccio Scalo

Physical Evidence

Recent modern research has cleared up the march of the chickens. Chicken bones are difficult to distinguish from other related species. Scavenger activity and stratigraphic displacement add to the opacity. Taxonomic classification is ambiguous. Chickens are as hard to find in the archeological record as hen’s teeth.

The earliest physical evidence of domesticated chickens were found in central Thailand. Chicken bones appear in grave goods in Ban Non Wat (~1038 to 950 BCE) and Ban Na Di (~ 800 to 500 BCE). There was a high proportion of juvenile bones in the findings. The bones were included with other domesticated animal remains, which indicate the domestication of chickens. Scholars speculate about a correlation of dry rice farming, millet, and other grains with the spread of chicken bones in Southeast Asia. This type of farming provides an environment that would attract the red jungle fowl out of the jungle.

There isn’t any physical evidence for chickens in the Indus valley. Chickens appear after the Harappan civilization. Other species of jungle fowl muddy up the trail.

The chicken is shown in a depiction in the temple area of Ishtar in Iraq in the late Bronze Age. Bones found across Mesopotamia and the Levant imply domesticated chickens were in the area. Increasing numbers of bones indicated their growing presence at sites from ∼965 to 530 BCE which aligns with the increasing appearance in the iconographic records. Images of chicken are present on a square stone in the wall of Tell Halaf (present day Syria) dated to ∼900 BCE and on numerous cylinder seals between ∼800 to 600 BCE.

Chickens are in Egypt during the Achaemenid period (∼550 to 330 BCE) evidenced by chicken remains that have been identified in lower Egypt. Under Ptolemaic rule (305 to 30 BCE), fowl husbandry intensified and spread from the Nile delta upstream to the region of the first cataract.

The current theory is that seafarers, perhaps the Phoenicans, took chickens with them in their journeys around the northern Mediterranean. The earliest chickens in southern Europe were excavated in Italy from two Greek colonies dated to 776 to 540 BCE. Chickens moved from North to South.

Chickens show up in Italy first in grave goods. Bones were found in the cinerary hut urn from the Montecucco necropolis (Castel Gandolfo, Rome) Central Italy in the 10th – first half of the 9th century BCE. This early Iron Age period is called phase IIA of the Latial Culture which overlaps the foundation of the Roman Kingdom.

The chicken remains found in the cinerary hut run from the Monterozzi necropolis were leg bones. The bones were heavily charred as if they were burned on the pyre with the deceased. It could have been an offering in some ritual for the dead.

Several sites in the Po Valley have chickens associated with grave goods.

- Benacci Capara grave 38 – 2nd half 8th c BCE

- Romagnoli grave 1, first half of the 7th century BCE

- Villanova Necrosis Caselle – 2nd 8th c BCE – found egg shells

Chickens were a part of Iron Age Italy, clucking and scratching about well before the Roman Republic. Chickens were in Italy by the early 5th century BCE. Etrustican alectryomancy was adopted by the Romans and chickens roosted in the Eternal City.

There is a very famous story of the Roman General Publius Claudius Pulcher. He asked the chickens about his upcoming battle while on his boat. Their answers didn’t please him and he chucked them all into the sea. Apparently he said, “Since they do not wish to eat, let them drink!”

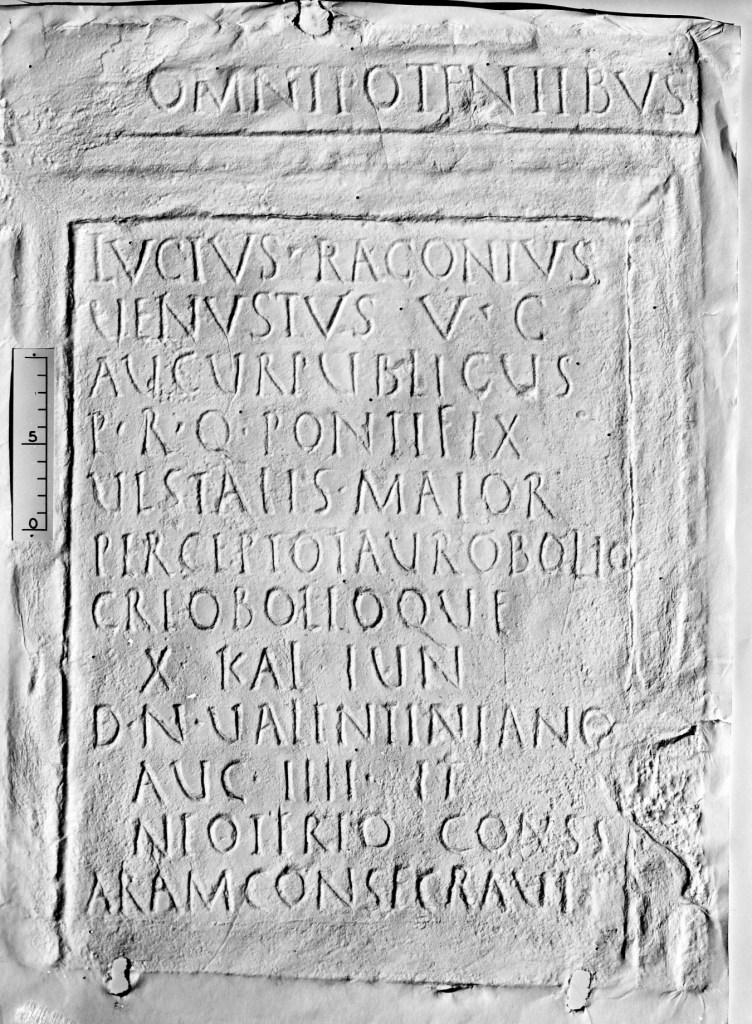

Sacred divining chickens disappear from history. The last augur mentioned in the Roman historical records was Lucius Ragonius Venustus. He dedicated an altar to Cybele and Attis with the sacrifice of a bull and ram on May 23, 390 CE. We’ll never know what he thought of chickens.

References

Best, Julia, et al. “Redefining the Timing and Circumstances of the Chicken’s Introduction to Europe and North-West Africa.” Antiquity, vol. 96, no. 388, 7 June 2022, pp. 868–882, https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2021.90.

Britain, Roman, and Michael Feider. Chickens in the Archaeological Material Culture Of. 2017.

“Cock-a-Doodle-DOOM: The Sacred Chickens of Ancient Rome and the Risks of Ignoring Them.” History Skills, 2014, http://www.historyskills.com/classroom/ancient-history/sacred-chickens/#. Accessed 25 Nov. 2024.

Corbino, Chiara Assunta, et al. “The Earliest Evidence of Chicken in Italy.” Quaternary International, vol. 626-627, July 2022, pp. 80–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2021.04.006. Accessed 26 May 2022.

Cosette. “Ornithomancy and How to Read Messages from Birds.” Divine Hours Priestess & Tarot Reader, 17 Mar. 2023, cosettepaneque.com/ornithomancy-and-how-to-read-messages-from-birds/. Accessed 25 Nov. 2024.

Dozier, Terry . “The Symbolism of the Rooster.” New Acropolis Library, 22 Sept. 2014, library.acropolis.org/the-symbolism-of-the-rooster/.

Fisher, Martini. “Augurs of Rome, Masters of the Birds.” Martini Fisher, 24 May 2023, martinifisher.com/2023/05/24/augurs-of-rome-masters-of-the-birds/.

Hans, Luuk. Photo above Courtesy of Http://Www.summagallicana.it. 2009.

Harrsch, Mary. “Alectryomancy and the Sacred Rooster.” Blogspot.com, 2020, ancientimes.blogspot.com/2020/11/alectryomancy-and-sacred-rooster.html.

Lawler, Andrew. “How the Chicken Conquered the World.” Smithsonian, Smithsonian.com, June 2012, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-the-chicken-conquered-the-world-87583657/.

Louis, chevalier de Jaucourt (biography). “Sacred Chickens.” Encyclopedia of Diderot & d’Alembert – Collaborative Translation Project, quod.lib.umich.edu/d/did/did2222.0000.865/–sacred-chickens?rgn=main.

Peters, John W. “The Cock.” Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 33, 1 Jan. 1913, pp. 363–363, https://doi.org/10.2307/592841. Accessed 29 Apr. 2023.

Meddings, Alexander. “The Sacred Chickens That Shaped Rome’s Foreign Policy | Alexander Meddings.” Historycollection.co, 12 May 2020, alexandermeddings.com/history/the-sacred-chickens-that-shaped-romes-foreign-policy/.

Peters, Joris, et al. “The Biocultural Origins and Dispersal of Domestic Chickens.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 119, no. 24, 6 June 2022, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2121978119.

Piscinus, M. Horatius. “On Auguries.” Www.societasviaromana.net, http://www.societasviaromana.net/Collegium_Religionis/augury.php.

Sheridan, Paul. “The Sacred Chickens of Rome.” Anecdotes from Antiquity, 8 Nov. 2015, http://www.anecdotesfromantiquity.com/the-sacred-chickens-of-rome/.

sumerianlanguage. “I’ve Read That the Sumerians Had Chickens as Livestock, but I Can’t Find What They Called Them. Do You Know of Any Words Meaning Chicken or Poultry?” Tumblr, 29 Jan. 2024, sumerianlanguage.tumblr.com/post/740887858289803264/ive-read-that-the-sumerians-had-chickens-as. Accessed 25 Nov. 2024.

Trentacoste, Angela. “Fodder for Change: Animals, Urbanisation, and Socio-Economic Transformation in Protohistoric Italy.” Theoretical Roman Archaeology Journal, vol. 3, no. 1, 26 June 2020, p. 1, https://doi.org/10.16995/traj.414. Accessed 8 Nov. 2020.

Wikipedia Contributors. “Alectryomancy.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 22 Oct. 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alectryomancy.

Wood-Gush, D. G. M. “A History of the Domestic Chicken from Antiquity to the 19th Century.” Poultry Science, vol. 38, no. 2, 1 Mar. 1959, pp. 321–326, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0032579119480565, https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0380321. Accessed 26 Feb. 2022.

Leave a comment